Extreme precipitation—rain or snow events that far exceed typical amounts—is becoming more frequent and intense as the climate warms. Warmer air holds more moisture, increasing the likelihood of heavy downpours and associated hazards such as flooding, water quality issues, and landslides. Communities across the United States are already experiencing these growing risks as extreme precipitation trends accelerate.

Historical Conditions and Future Projections for Extreme Precipitation

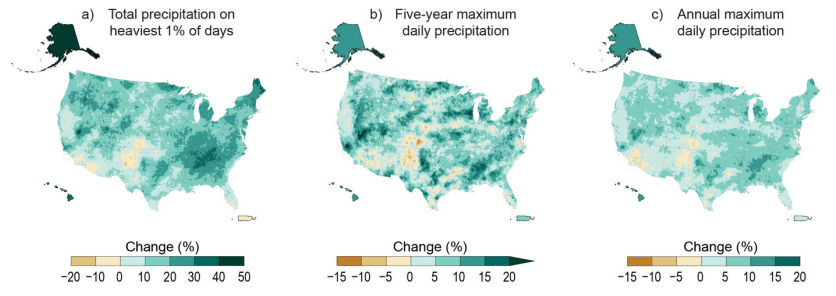

Extreme precipitation events have increased in frequency and intensity in the U.S. and across many regions of the world since the 1950s. These events are defined as instances in which the amount of rain or snow experienced in a location substantially exceeds what is normal. In the contiguous United States, annual precipitation has increased by 0.2 inches per decade since 1901, with extreme precipitation events outpacing this trend. The Midwest and Northeast have experienced the most substantial increases in heavy precipitation events.

Scientists expect these trends to continue as the planet warms. For each degree Celsius of warming, the air’s capacity to hold water vapor increases by approximately 7 percent. An atmosphere with more moisture can produce more intense precipitation events.

Increases in the frequency and severity of heavy precipitation may not always translate into higher total precipitation over a season or a year. Some climate models project a decrease in moderate rainfall and an increase in the length of dry periods, offsetting the effect of extreme precipitation events.