C2ES has been in conversation with cities, companies, asset managers, credit ratings agencies, and others working at the intersection of climate risk, economics, policy, and health or well-being. From these conversations, a few critical opportunities to be more resilient emerge:

- Adaptation costs money, the primary barrier for communities. More diverse funding sources and innovative finance mechanisms are needed to encourage private and public funders to invest in resilience projects. These could include a national infrastructure bank, loan programs, and tax incentives for companies and individuals.

- Many communities are identifying risks and developing resilience or adaptation plans, but for those who have already taken these steps, it’s time to get to work. Different non-structural and infrastructure solutions need testing, so more funding and support should be available for implementing and monitoring their success. Practitioners should work with the federal government and private sector to develop ways to measure success and promote projects that can be adjusted if they are not effectively addressing risk or have unintended consequences.

- While communities and companies are taking steps to implement easier steps of their adaptation plans, it’s time for a longer-term discussion about how property buyouts and migration may affect community preparedness. States and cities are beginning to acknowledge the possible need for retreat (e., limiting or removing residences in risky areas), but because it could affect large coastal areas, disproportionately displace low-income and long-term coastal residents, and trigger inter-state migration, this should be coordinated on a national level.

- Any pre-disaster mitigation or resilience initiative should include provisions for low-income households, communities of color, or otherwise vulnerable populations. This includes the efforts at the federal level. This is especially important following a March 2019 report from NPR that found disaster aid and funds to “buy out” vulnerable properties are overwhelmingly used for affluent communities and individuals. As we shift to more proactive risk management, there is opportunity to also address these inequities before disasters.

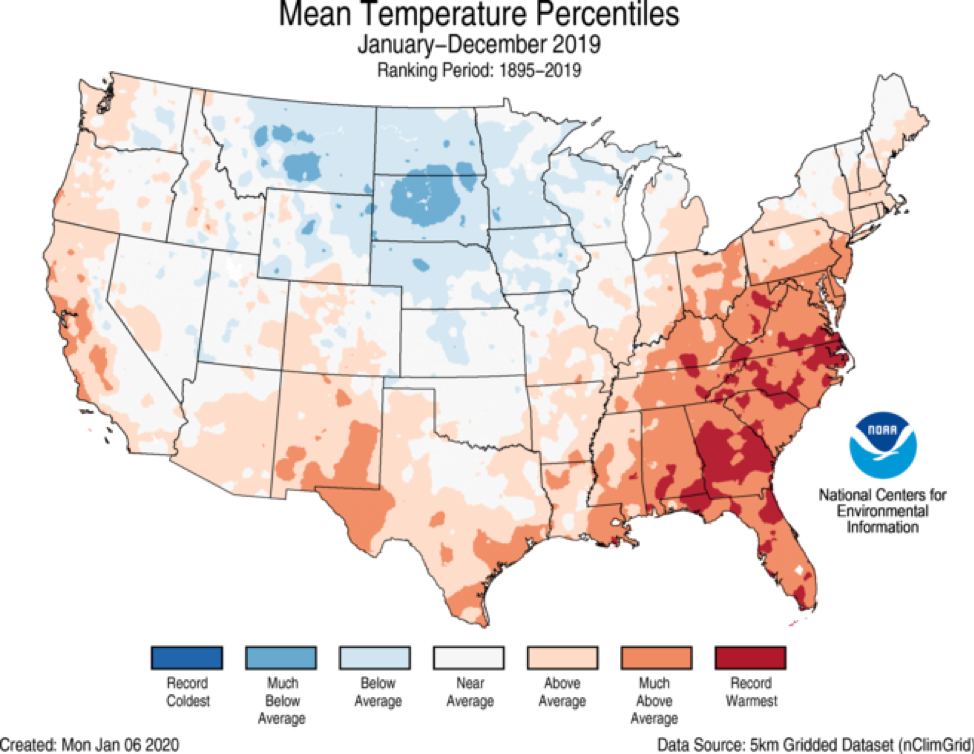

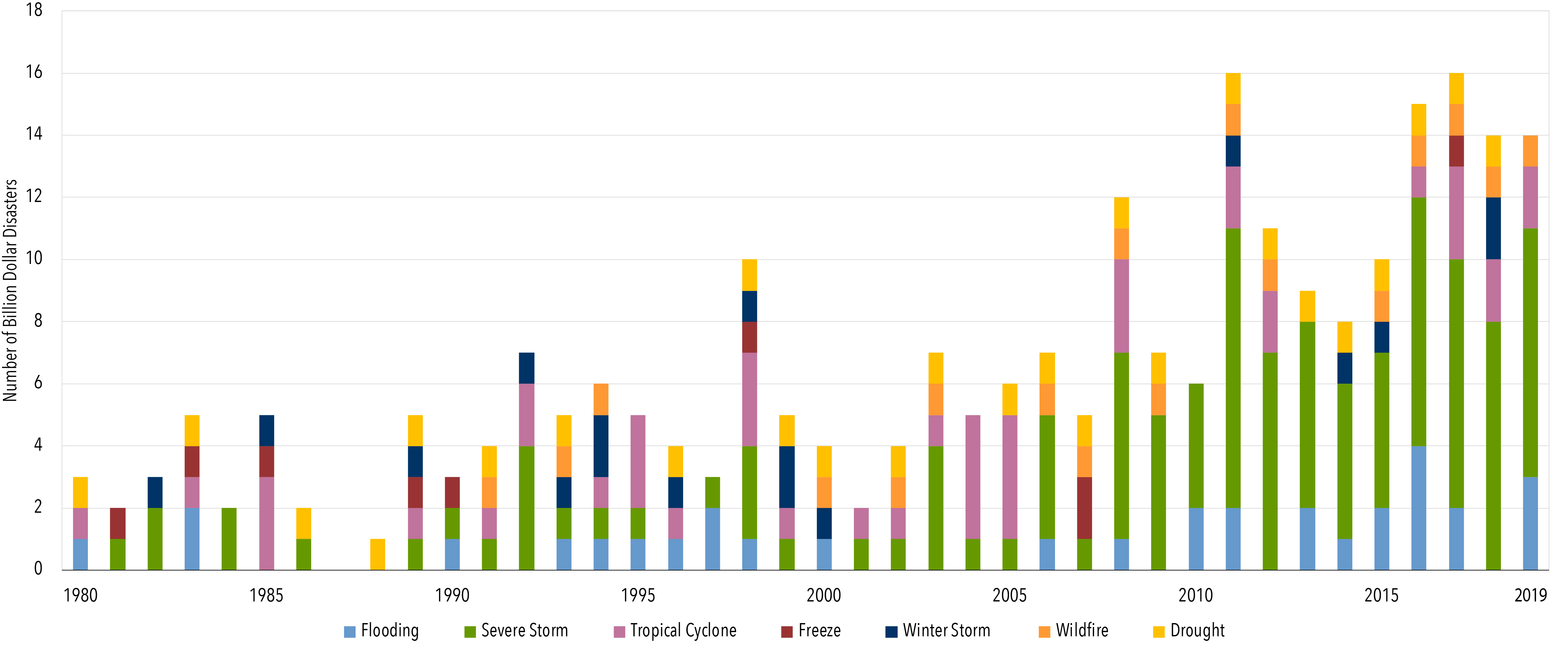

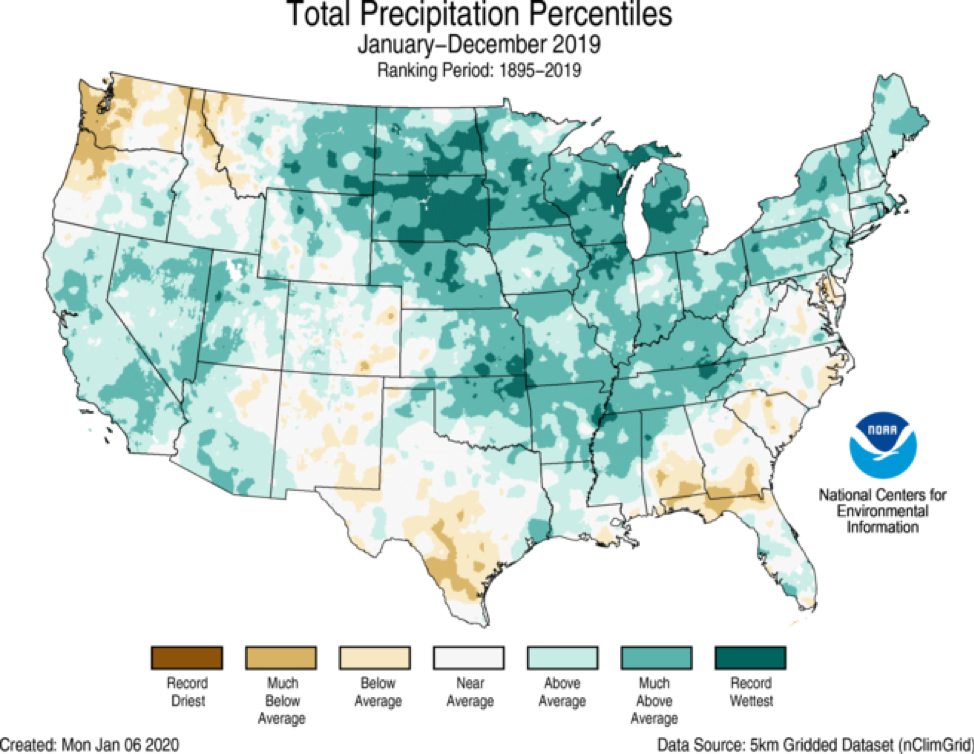

Now, in 2020 and looking ahead to 2021, as a new Congress and presidential term begin, is the time to coalesce around resilience and adaptation action. Much stronger federal focus is needed on rural as well as urban communities, especially those facing flooding and extreme heat. Less severe events like repeated flooding, as well as extreme events like hurricanes, deserve increased attention. The increasing price of events outlined above is falling on states and local governments, with significant financial impacts on the federal government and businesses. With those impacts comes loss of economic vitality and competitiveness.

To avoid these consequences, federal leadership on adaptation policy is crucial to enhance state, local, and private sector action. High priorities for the president and Congress should include incentives to increase coordination of cross-boundary climate resilience actions and planning to help reduce future costs, private-sector engagement with state and local governments, and support for local action with resources, project funding, and guidance.