We’ve all seen tragic and expensive weather disasters, like hurricanes, tornadoes, and floods inflict terrible economic and personal damage on a region in just a few hours or days. But another billion-dollar U.S. weather disaster is playing itself out over the course of the year, with potential bad news for the entire economy.

Months of rain nationwide severely delayed planting of the U.S. corn crop, which accounts for 95 percent of the nation’s feed grain for livestock. On top of that, a heat wave moving across the country is further threatening even more destruction. Already weakened by late planting and a rainy spring, crops are more vulnerable to extreme changes in weather. If the moist soil dries too quickly and becomes too compact, roots will not develop properly and the plants won’t grow. The result could be higher prices for most foods, vehicle fuel, and other consumer products — a major hit to the wallets of most Americans.

Now comes research showing this could be a trend. A study out this week from the U.S. Department of Agriculture warns that unchecked climate change could lead to more frequent extreme weather like this year’s, threatening the future of future corn, soybean, and wheat crops.

Each year in April and May, corn farmers sow millions of acres. This year, however, most of that time was spent idle, as rain poured across the Corn Belt, from Ohio to the Dakotas and from the Missouri Valley to the Canadian border. The wettest 12 months on record for the continental United States turned valuable farmland into acres of muck, where farm equipment couldn’t operate and seeds wouldn’t grow.

Soil needs to dry for at least a week after such rain, and the wet weather didn’t let up long enough or early enough. Above average rain in last summer and fall meant that water-saturated soil froze over the winter. Snow melted in March before the ground could thaw, meaning none of the snowmelt could soak through the soil. Instead it ran across the surface of the ground, adding to the flooding from rain.

On June 10, well past the time most farmers would typically plant, the U.S. Department of Agriculture reported only 83 percent of the nation’s corn acreage had been planted. The typical amount for that time of year is 99 percent. In some states, the news was much worse: Ohio farmers had only half their crop in the ground, Indiana’s had 67 percent, and in Illinois, the total was 73 percent.

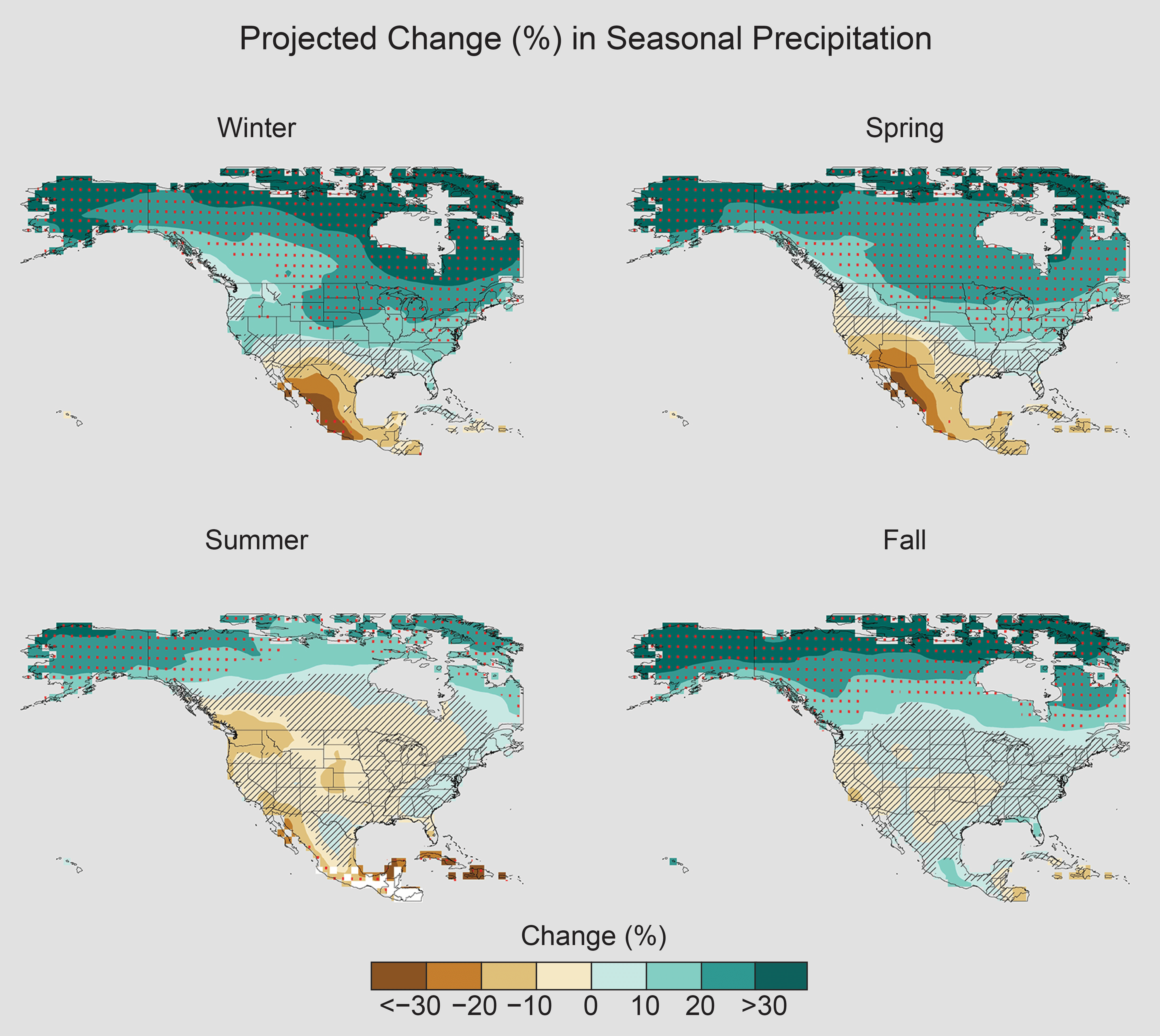

Scientists say the overall rainy weather is the result of climate change. Donald Wuebbles, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, tells NatGeo that the past year’s increase in total precipitation in the Midwest, especially in winter and spring, is in line with what he’s been predicting, with more falling in larger extreme weather events. David Easterling, the chief of the scientific services division at the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration, says it’s a trend his agency helped predict in the most recent National Climate Assessment, published in 2018.