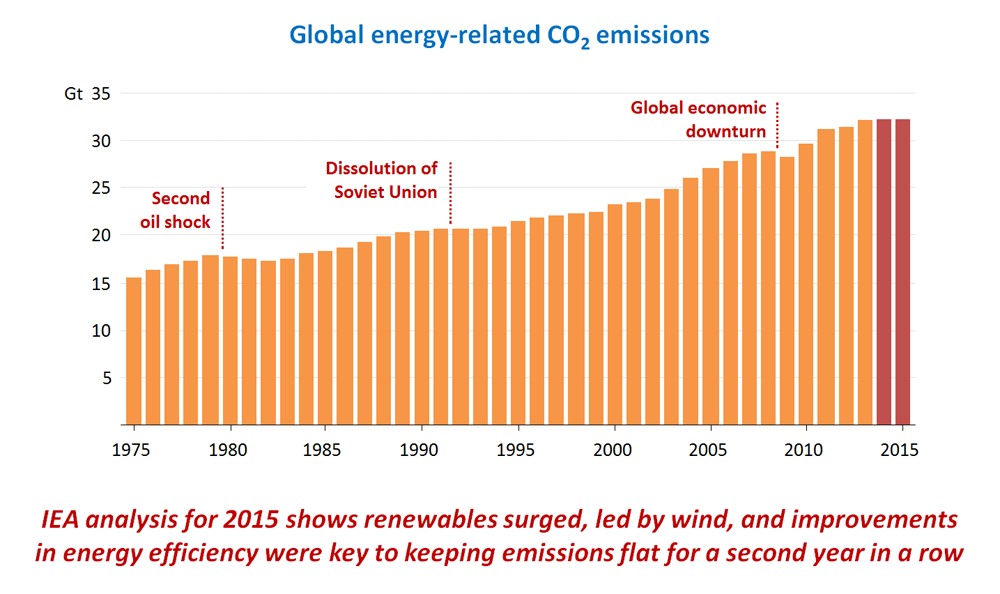

For the second year in a row, the global economy grew and global carbon dioxide emissions did not.

Preliminary data from the International Energy Agency (IEA) indicate that energy-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions (from burning fossil fuels for electricity, transportation, industry, space heating and so on) remained unchanged from the previous two years at around 32.1 billion metric tons. Meanwhile, economic growth increased by more than 3 percent for the second consecutive year.

A couple years of data doesn’t necessarily translate into a trend. And continued ambition in the decades ahead – like we saw with the landmark Paris Agreement in December 2015 – will be required before we can announce that we have truly turned the corner on reducing CO2 emissions.

But the IEA noted that 90 percent of new electric generation in 2015 came from renewables. Yes, 90 percent. And this apparent decoupling – after decades of energy-related CO2 emissions moving in lockstep with economic growth — is a positive sign that low-carbon policies may finally be gaining traction in many parts of the world.

The change is due to policies and market forces affecting two factors – energy intensity and fuel mix – both in China and in the developed economies.

Energy intensity is a measure of how much energy a country uses to create its goods and services, or GDP. Fuel mix looks at what sources, such as fossil fuels, nuclear and renewables, a country uses to derive its energy.

In China, efficiency policies, ambitious targets for renewable and nuclear energy, and anti-pollution measures appear to be having the desired effect. Though estimates vary, CO2 emissions in China last year dropped for the first time, by 0.5 to 1.5 percent, even as its economy grew 6.9 percent.

China, the world’s largest energy consumer and largest emitter of CO2, has committed to reducing its energy intensity, setting goals in its last two five-year plans. China’s energy intensity will decline as it transitions from a predominantly manufacturing economy to a more service-based economy. Chinese coal consumption fell by 3.7 percent last year due to its economic transition as well as a shift to new, cleaner electric generating capacity, restrictions on where new coal plants can be built, and shutdowns of older, less efficient plants in urban areas.

In developed countries, policies to promote energy efficiency and increase the adoption of renewable electricity generation seem to be paying off. CO2 emissions in developed countries peaked in 2007 and were nearly 7 percent lower in 2012, even as economic activity increased after 2010.

Developed countries have reduced energy intensity by improving vehicle fuel economy and increasing the efficiency of appliances and industrial and commercial equipment. U.S. fuel economy standards adopted in 2012 for model years 2017 to 2025 will double the efficiency of the U.S. fleet compared with vehicles manufactured in 2008, lowering emissions. Moreover, the United States, the European Union, Japan and many other countries are encouraging greater adoption of more efficient lighting, refrigerators, and industrial equipment, reducing electricity consumption.

In the U.S., 30 states and the District of Columbia have renewable electricity standards, which, along with other national policies, are encouraging greater quantities of renewable generation. Since 2002, non-hydro renewable electricity generation in the United States has more than tripled.

Market forces have also contributed to decarbonizing the fuel mix, particularly in the United States. An abundance of natural gas has led to its greater use in the power sector. Since 2005, natural gas’ share of the U.S. electricity mix has increased from 19 to 33 percent, while coal’s share has gone from 50 to 33 percent. Since burning natural gas releases half as much carbon dioxide as burning coal (and far fewer pollutants per unit of energy), the shift to natural gas plus growing renewable generation lowered U.S. power sector emissions 18 percent.

While these developments are promising, the IEA’s own projections show we’re not likely to stay on this path, and that global CO2 will increase in the future. The World Energy Outlook 2015’s more optimistic scenario projected energy-related CO2 emissions will rise 5 percent by 2020 and 10 percent by 2030, led by emissions growth in developing countries. Non-CO2 greenhouse gases are also expected to increase, and land-use changes and deforestation could also worsen the problem. This projection was released in November and does not include the effect of Paris climate pledges.

Clearly, there is more work to do.

But there’s reason to be optimistic, especially as more than 180 countries representing 98 percent of global emissions begin implementing their intended contributions to the Paris Agreement. Greater adoption of policies that reduce energy intensity, promote energy efficiency, and decarbonize our fuel mix will help countries, states, cities, and companies reduce emissions and limit the harm from climate change.