This paper introduces the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions’ (C2ES) Innovation Policy Matrix, a user-friendly, nonpartisan, and technology-neutral tool designed to help policymakers assess and craft effective innovation policy. The framework synthesizes four interrelated components that, when applied together, enable policymakers to efficiently develop a comprehensive understanding of the policy needs for any given technology and the broader innovation ecosystem. The tool creates a standardized snapshot of where any given technology sits along the innovation process, the barriers hindering the broader ecosystem, and the key risks to prioritize when developing policy solutions. Risk is an intrinsic part of innovation, so the public and private sectors should play complementary roles as risk takers and risk managers. In particular, the federal government can play an important role as a risk-tolerant supporter of innovation, especially when technological feasibility and market applications are still unclear. This matrix was informed by the insights generated from over two years of the C2ES technology working groups program, which includes more than 140 companies across the innovation ecosystem.

Click here for the two-pager of the C2ES Innovation Policy Matrix.

The federal government has long played a pivotal role in shaping the pace and direction of American innovation. Since Vannevar Bush led the Office of Scientific Research and Development during World War II—an effort that led to the establishment of the National Science Foundation—government-backed initiatives have been instrumental in fostering the development and derisking of technological advancements that have been critical in addressing our nation’s economic and security needs. Federal policy support made nuclear power, solar photovoltaics, and hydraulic fracturing for oil and gas extraction possible, to name just a few. This sustained commitment to innovation has been a key driver in making the United States the world’s largest and most dynamic economy.1David C. Mowery and Nathan Rosenberg, Technology and the Pursuit of Economic Growth (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1991), https://knowledge4all.com/admin/Temp/ Files/27051307-d32a-4570-b77a-31fc4fc2d92a.pdf; see also National Research Council of the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine, Rising to the Challenge: U.S. Innovation Policy for the Global Economy (Washington, D.C., The National Academies Press, 2012), https:// nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/13386/rising-to-the-challenge-us-innovation-policy-for- the-global; see also Charles I. Jones, “The Past and Future of Economic Growth,” Annual Review of Economics 14 (April 2022), https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev- economics-080521-012458.

The United States is currently in a period of accelerated innovation, with a growing suite of new technologies popping up across an expansive range of industries. This includes recent breakthroughs in nuclear fusion, geothermal, artificial intelligence (AI) processing power, and a vast ecosystem of compelling new clean technologies. These innovations have the potential to contribute to the United States’ energy abundance, enable the resurgence of domestic manufacturing and associated supply chains, reduce pollution and emissions, and solidify the United States’ position as a global leader in innovation as the world moves toward a low-carbon economy. However, this potential is contingent on whether technologies can successfully progress through the innovation process and achieve widespread commercial deployment. Indeed, innovators must resolve key technical and economic risks, progress down the cost-curve, and unlock private capital to reach commercial scale. Well-crafted innovation policy can expedite and facilitate this process while crowding in private sector investment and ensuring the targeted and appropriate assumption of risk for public resources.

Today, policymakers are navigating many exciting, yet challenging, questions: What are the key scientific, technical, and economic risks for these technologies that will require additional federal support? Where could federal support or regulatory certainty help unlock more private sector capital? What is the balance between providing sufficient policy certainty for investors and innovators while avoiding perpetual subsidies? How should the federal government balance targeted efforts to address critical gaps wherever they may exist across the innovation ecosystem, including improvements that follow initial adoption, while still ensuring that the free market ultimately determines the most competitive technology solutions?

In 2023, C2ES established working groups aiming to develop a comprehensive view of both innovation bottlenecks and the tools available to release them, with a focus on four promising low-carbon technologies: engineered carbon removal (ECR), sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), long-duration energy storage (LDES), and clean hydrogen. The four technologies were selected due to their potential significance to the U.S. economy and to achieving net-zero goals, as well as their ability to enhance domestic energy security and maintain U.S. competitiveness in innovation. Across the four technology working groups, C2ES has convened more than 140 startups, investors, Fortune 500 companies, utilities, and supporting infrastructure players to discuss and identify the market and policy solutions needed to enable the progression of these technologies through the innovation process.

Drawing on insights shared by this diverse set of perspectives across the technology commercialization ecosystem, this paper presents a technology-neutral framework to help policymakers evaluate the key risks emerging technologies face and determine the appropriate role and design of federal policy in supporting both current and future innovations. The paper begins with a brief introduction to innovation and the C2ES technology working groups and then provides an overview of each of the four components of the matrix, before concluding with an illustrative example.

Innovation is a key driver of economic growth and historically has helped the United States create new industries and capture leadership in them.2 Michael J. Andrews et al., The Role of Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Economic Growth (Chicago, I.L.: The University of Chicago Press, 2022), https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/ chicago/R/bo151022289.html. Each additional dollar of government-funded research and development (R&D) returns an estimated $2–5 in gross domestic product (GDP) growth.3Matt Clancy, “Frequently Asked Questions About US Government Funding for R&D,” New Things Under the Sun, February 19, 2025, https://www.newthingsunderthesun.com/pub/d4ggviu4/ release/2#whats-a-reasonable-guess-at-the-marginal-rather-than-average-roi-of-government-rd These returns rise considerably when hard-to-measure social benefits, like improved health and national defense, are added to the ledger.4Ibid Beyond their economic impacts, American innovation in clean technologies has substantially reduced environmental externalities, like air pollution, and delivered measurable public health gains. For instance, advances in cleaner combustion technologies and scrubbers on power plants have cut U.S. particulate matter concentrations by 32 percent since 1990, helping to prevent premature deaths each year and reduce the burden of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases across the country. Clean technologies will continue to help reduce risks to lives and livelihoods, while also strengthening U.S. competitiveness and unlocking economic opportunities in communities across the country.5“Ambient Concentrations of Particulate Matter,” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, accessed July 2, 2025, https://cfpub.epa.gov/roe/indicator.cfm; see also “Health and Environmental Effects of Particulate Matter (PM),” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, accessed July 2, 2025, https://www. epa.gov/pm-pollution/health-and-environmental-effects-particulate-matter-pm

Clean technology industries are also fiercely competitive, with China establishing a dominant position and the European Union, Japan, South Korea, and many other countries responding with industrial strategies of their own.6Bentley B. Allen and Jonas Nahm, “Strategies of Green Industrial Policy: How States Position Firms in Global Supply Chains,” American Political Science Review Journal 119 (May 2024), https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-political-science-review/article/ strategies-of-green-industrial-policy-how-states-position-firms-in-global-supply-chains/ BB673EA2C45CA650F164B678393F9913. China in particular is quickly closing the innovation advantage the United States has built over decades. Chinese investments in clean energy make up one-third of all global investments, and exports of solar cells, lithium batteries, and electric vehicles comprise a major and growing part of their trade strategy.7“World Energy Investment 2024: China,” International Energy Agency, accessed June 10, 2025, https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-investment-2024/china Meanwhile, the European Union is implementing a carbon border adjustment mechanism spanning most carbon-intensive industries to help support its clean technology innovation efforts.8Antoine Dechezlepetre, et al., What to expect from the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism?, (Paris, France: OECD, 2025), https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/what-to-expect- from-the-eu-carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism_719d2ff9-en.html A favorable innovation environment benefits not only domestic innovators, but can also attract international businesses, investors, and talent. An ‘innovation drain’ for one country is often an ‘innovation gain’ for another. The United States is not immune to this dynamic. Unfavorable or insufficient domestic policy could lead to an exodus of innovation and talent to other countries with more supportive innovation policy regimes.

The U.S. innovation ecosystem, built on nearly a century of public and private investment, has created several key competitive advantages, including world-class research institutions, robust capital markets, and a strong legal system that honors contracts. Together, these advantages provide a foundation that will allow the United States to win these industries of the future if they are properly leveraged to more efficiently create and scale world-class clean technologies. Smart policy, grounded in the real-world experience of innovators, financiers, and other private sector partners, can more effectively unlock opportunities for research, development, deployment, and diffusion, as well as the private capital needed to scale these technologies and win the innovation race.

The diverse perspectives represented across C2ES’s four technology working groups helped shape this Innovation Policy Matrix. Each working group focuses on a technology with significant environmental and economic potential, as well as an ability to enhance energy security and maintain U.S. competitiveness in innovation. The working groups include startups, incumbent technology actors, corporate buyers, institutional investors, and supporting infrastructure providers.

The mission of the technology working groups is to convene the innovation ecosystem to examine key barriers to commercialization and identify the market and policy solutions needed to help accelerate deployment. In developing policy recommendations for each of the working groups, four key principles of policy design emerged. These principles capture invaluable insights drawn from the experiences of each working group and represent a critical component of the matrix.

Each of the four technologies offers environmental co-benefits beyond their potential for emissions reduction or removal. For instance, some ECR approaches can reduce wildfire risk, increase crop productivity, and mitigate ocean acidification. Deploying LDES relieves pressure to expand the physical grid, thereby minimizing land and habitat disruption and protecting ecologically sensitive areas and wildlife habitats from the impacts of large-scale energy deployment. SAF, including e-fuels produced with clean hydrogen, can reduce particulate matter and sulfur dioxide emissions from jet exhaust—pollutants associated with cardiovascular and respiratory diseases.

If successfully commercialized and scaled, each of the four technologies of C2ES’s working groups holds substantial potential for driving important economic outcomes:

The C2ES Innovation Policy Matrix synthesizes and builds on the latest thinking in innovation policy.9 See Jetta L. Wong and David Hart, Mind the Gap: A Design for a New Energy Technology Commercialization Foundation (Washington, DC: Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, 2020), https://d1bcsfjk95uj19.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/2020-mind-gap-energy-technology. pdf It incorporates four interrelated components that, when evaluated together, can help policymakers develop a comprehensive understanding of the policy needs for any given technology and the broader innovation ecosystem. The matrix seeks to introduce sufficient complexity to reflect real-world conditions, while maintaining a user-friendly and intuitive four-by-four model: four key risks, four innovation process stages, four ecosystem functions, and four policy design principles (see Figure 1). We introduce these concepts briefly here and then elaborate on each of them in the following sections.

Innovators are constantly navigating risk, from the earliest stages of research, through to large-scale commercial deployment. The nature of risk also changes over time and evolves alongside the innovation. The goal of federal innovation policy should not be to fully shoulder all the risk inherent in innovation. Rather, the objective should be to provide sufficient policy certainty and risk management to make capital investment attractive for private actors when the opportunity is right. The level and type of risk a company is willing to assume depends on its own risk tolerance, business model, and how effectively federal policy mitigates key uncertainties. For example, an institutional investor may be more comfortable taking on financing or commercial and management risks if public policy has already reduced the initial science and engineering risks. The federal government is often better positioned to absorb those initial risks because it operates on longer time horizons and with broader societal objectives than private actors, who typically face shorter payback expectations and fiduciary obligations to shareholders.

The task of policymakers is to support and enable a vibrant innovation ecosystem in which private sector risk-taking is maximized through the public sector appropriately taking on risks the private sector cannot. Additionally, the goal is not for every technology to succeed, but to create an environment in which the best technologies do. This, of course, is easier said than done.

The key risks that must be managed within an innovation ecosystem include:

For the sake of simplicity, this matrix limits its focus on risk to the four listed above and embeds them into the two next sections below.

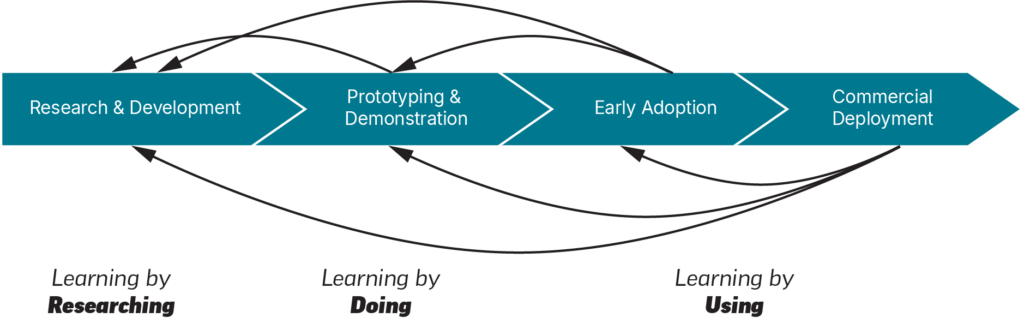

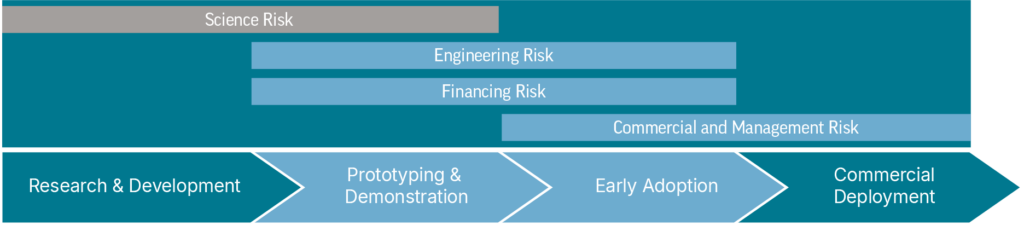

Innovations typically proceed through a series of stages as sketched out in Figure 2. The process can be very rapid, as is common in the software and internet industries, or it may take many years or even decades, as has typically been the case in capital-intensive heavy industries, like energy, infrastructure, and transportation. This latter type of industry is the focus of our technology working groups, which are all hard-tech innovations that require large-scale development, engineering, and construction.

It is important to note that scaling innovation is often a non-linear process. The learning generated at each stage of the innovation process, represented by the arrows in Figure 2, can provide valuable guidance for the others. These different learning cycles—denoted at the bottom of the figure as ‘learning by researching,’ ‘learning by doing,’ and ‘learning by using’—illustrate how knowledge gained in one phase can inform others. For example, the prototyping & demonstration stage may reveal technical challenges that R&D must address before an innovation can advance further. Similarly, as production scales to meet the needs of early adopters, supply chain constraints may reveal that alternative inputs will be needed for successful commercial deployment. Even during commercial deployment, late adopters may uncover new applications that were not anticipated in earlier stages, requiring prototypes to be revisited. These feedback loops create a virtuous cycle of learning that can help drive down costs, create economies of scale, and clarify the long-term revenue drivers and use cases for the innovation.

Research & Development

The R&D stage of the innovation process involves identifying problems and brainstorming solutions to address them. This stage focuses on conducting scientific, technical, or market research with the goal of developing prototypes to be tested in the next stage of the innovation process, prototyping and demonstration. During the R&D stage, scientists and inventors—whether working in corporate, government, or university laboratories, or independently in the proverbial garage—play a core role. These actors generate new ideas and explore their potential value in practice. While private sector support for R&D is needed, government funding is critical, as it drives progress in areas that may not yield immediate profits for companies but are vital to society, such as national security, public health, and clean energy. Innovation policies supporting this stage of the innovation process include federal funding for R&D projects and testbeds at national laboratories and universities.

Prototyping & Demonstration

Next comes the prototyping and demonstration phase of the innovation process, where ideas developed during R&D are transformed into tangible products, models, or systems for testing. In this phase, prototypes are developed, tested, and refined by entrepreneurs, investors, and builders to evaluate their performance and feasibility. Demonstrations provide proof-of-concept, showing how the innovation works in practice and whether it can meet real-world needs. An example of an innovation policy that supports this stage of the innovation process is cost-shared demonstration projects between the federal government and the private sector. Such policies are designed to bridge the “missing middle”—the gap between early R&D, where public funding predominates, and the later stages of the innovation process, where private capital typically steps in.

Early Adoption

The third stage of the innovation process is early adoption, where proven technologies begin to move beyond controlled prototypes and demonstrations into initial markets. In this stage, early adopters—often niche industries, specialized users, or governments—begin deploying first-of-a-kind commercial-scale projects. While end users play an important role throughout the innovation process, their feedback and support are especially influential in shaping the direction and pace of innovation during this phase. Innovation policies that support early adoption include tax credits, grants, and federal procurement programs, which help reduce costs and build market confidence.

Commercial Deployment

Commercial deployment is the final stage of the innovation process, where technologies move from early adoption into widespread use across mainstream markets. As innovations progress from first-of-a-kind deployment to nth-of-a-kind deployment, they may begin to achieve economies of scale. During this stage, manufacturers and technology users play central roles, addressing remaining challenges in production and application. Their efforts focus on achieving key performance and financial milestones needed for scaling, while also strengthening supply chains and developing new markets. Many policies that support early adoption by creating demand, such as procurement programs and tax credits, also help advance the last stage of the innovation process. Broader demand-side policies, such as carbon pricing and other market-based approaches like clean energy standards, can also support deployment. Actions that provide regulatory certainty, such as streamlined permitting processes, can play a crucial role as well.

Mapping Risks onto the Innovation Process

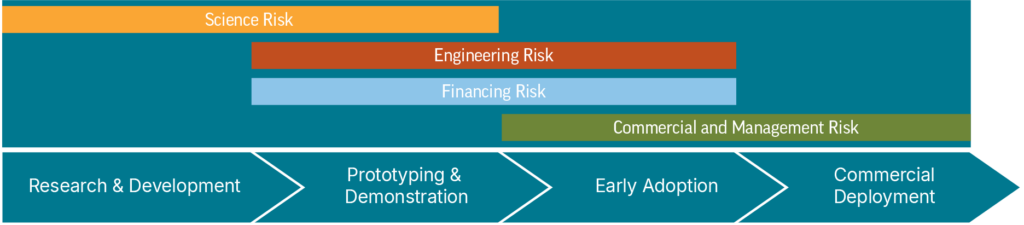

Each stage of the innovation process carries a distinct risk profile, and well-designed innovation policies can help mitigate these risks (see Figure 3). For example, science risk is most prevalent during the R&D and prototyping & demonstration stages, where new ideas and technologies must be proven viable. Engineering risk becomes especially prominent during prototyping & demonstration and continues into early adoption, as technologies are tested, refined, and scaled. Financing risk arises throughout the innovation process but may be particularly severe in the prototyping & demonstration and early adoption stages, where the “missing middle” funding gap occurs. Commercial and management risk is most significant in the early adoption and commercial deployment stages, when innovations must compete in the marketplace, secure supply chains, and demonstrate long-term value.

It is important to note that these risks may also be present outside of the specific stages identified, given the interrelated nature of the innovation process. However, this categorization can serve as a productive initial filter for policymakers as they seek to address the risks impacting technologies at different stages.

The innovation process does not occur in a vacuum and is shaped by broader dynamics and actors in the innovation ecosystem. Federal policy and regulation do not act alone; private markets, information flows, and social norms all inform an innovation’s path toward commercial deployment. Private markets provide financial incentives and encourage competition between firms and individuals participating in the innovation process. Information flows drive the exchange of data and ideas between actors and processes. Social norms can impact adoption by positively or negatively sanctioning users of a given innovation.

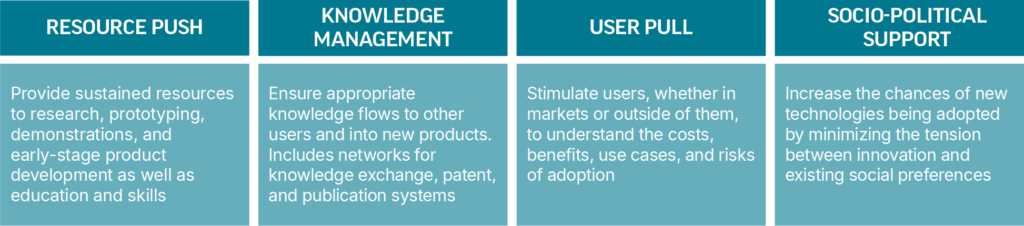

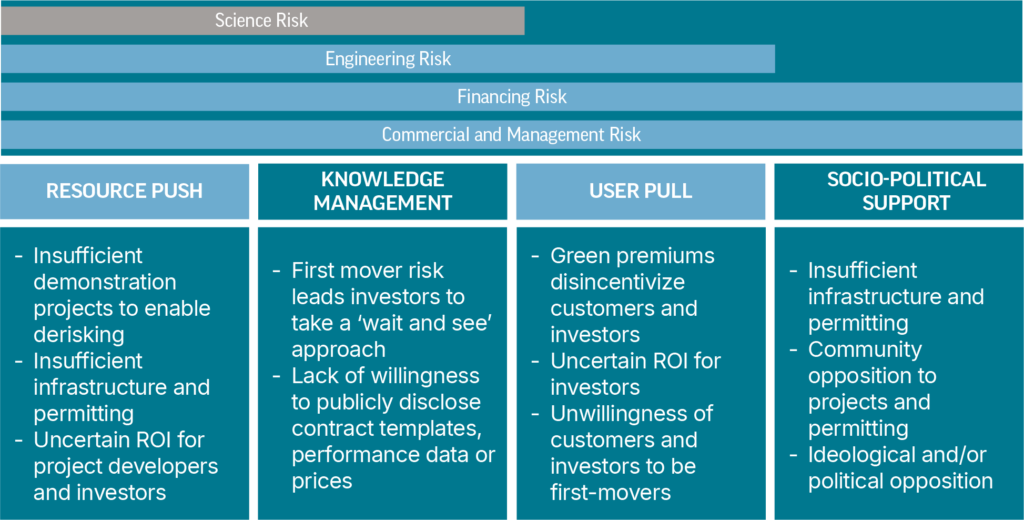

It is critical for policymakers to understand these dynamics because they provide valuable information on the behaviors of ecosystem actors and the nature of potential barriers to innovation. Succinctly capturing so much complexity is challenging, but the International Energy Agency effectively characterized these using their “Four Pillars of Effective Energy Innovation Systems.”14Adapted from International Energy Agency, Energy Technology Perspectives 2020: Special Report on Clean Energy Innovation (Paris, France: International Energy Agency, 2020), https://iea. blob.core.windows.net/assets/04dc5d08-4e45-447d-a0c1-d76b5ac43987/Energy_Technology_ Perspectives_2020_-_Special_Report_on_Clean_Energy_Innovation.pdf Each of these pillars represents a distinct function of the innovation ecosystem. When barriers obstruct one or more of the four functions, the innovation process begins to slow or stall. These four functions—resource push, knowledge management, user pull, and socio-political support—are the third component of the C2ES Innovation Policy Matrix (see Figure 4).

Resource Push

Resource push is focused on ensuring the sustained provision of resources, education, and skills to support developers along the innovation process. Actors involved in the innovation process need money, equipment, talent, and other resources to do their work. Relatedly, those with resources seek opportunities to advance innovation by supporting technology developers. Private, public, and philanthropic investors who perform the resource push function have different motivations and place different weights on the risks being addressed. For example, public and philanthropic funders may support R&D projects that contribute to public welfare and are happy to absorb science risk, while the limited financial rewards from taking such risks often deter private investors. Public and philanthropic funders may also want to support prototyping and demonstration to reduce engineering and financing risks for later-stage private investors.

Like federal funding for R&D, tax incentives for private R&D spending and public-private demonstration partnerships are innovation policies that allow risks to be shared among types of investors who have different tolerance levels for different risks, but whose combined investments enable R&D and demonstration projects to happen.

Knowledge Management

Knowledge management impacts all the learning feedback loops (i.e., learning by researching, doing, and using) and ensures that new knowledge flows to other users and new products. This function is impacted by norms and laws related to secrecy, disclosure, and property rights, which may incentivize or disincentivize actors to share or withhold knowledge. Some first movers are concerned with carrying out engineering and commercial activities that are costly to them while benefiting fast followers who can learn from the first movers’ successes and failures. This is also known as knowledge spillover. Adjustments to intellectual property or trade secrecy law may remove this barrier.

In other cases, advances that would benefit an entire industry are blocked by antitrust laws that restrict competitors from sharing knowledge. Exceptions to these laws for innovative joint ventures among competitors can enable progress.

User Pull

User pull stimulates both innovators and users to accurately understand the costs, benefits, use cases, and risks of adoption. These factors are often determined by markets, which aggregate individual decisions to inform producers about the scale and type of demand for the innovation. Novel innovations that must compete with legacy incumbents are particularly vulnerable to weak user pull, especially when potential users are cost sensitive and risk averse.

Innovation policies that support this function include tax incentives for customers to help kickstart market demand, government procurement to help shoulder the higher initial costs of new technologies, and regulatory mandates that level the playing field for all users.

Socio-political Support

Socio-political support impacts every stage of the innovation process and every other function of the innovation ecosystem. Such support—or disapproval—may be expressed in the media, public policy, and day-to-day social interactions with knock-on effects on the availability of resources, knowledge flows, and adoption decisions. The socio-political support function tends to come to the fore in later stages of the innovation process, as a much larger portion of the population becomes aware of and may be impacted by the innovation.

Public engagement that provides broad education about the benefits, costs, and risks of the innovation, and allows members of the public to have a voice in the deployment process, may address this challenge. Community benefits plans and public infrastructure funding that shift the balance of benefits, costs, and risks may also deepen socio-political support for an innovation.

Mapping the Risks onto the Ecosystem Functions

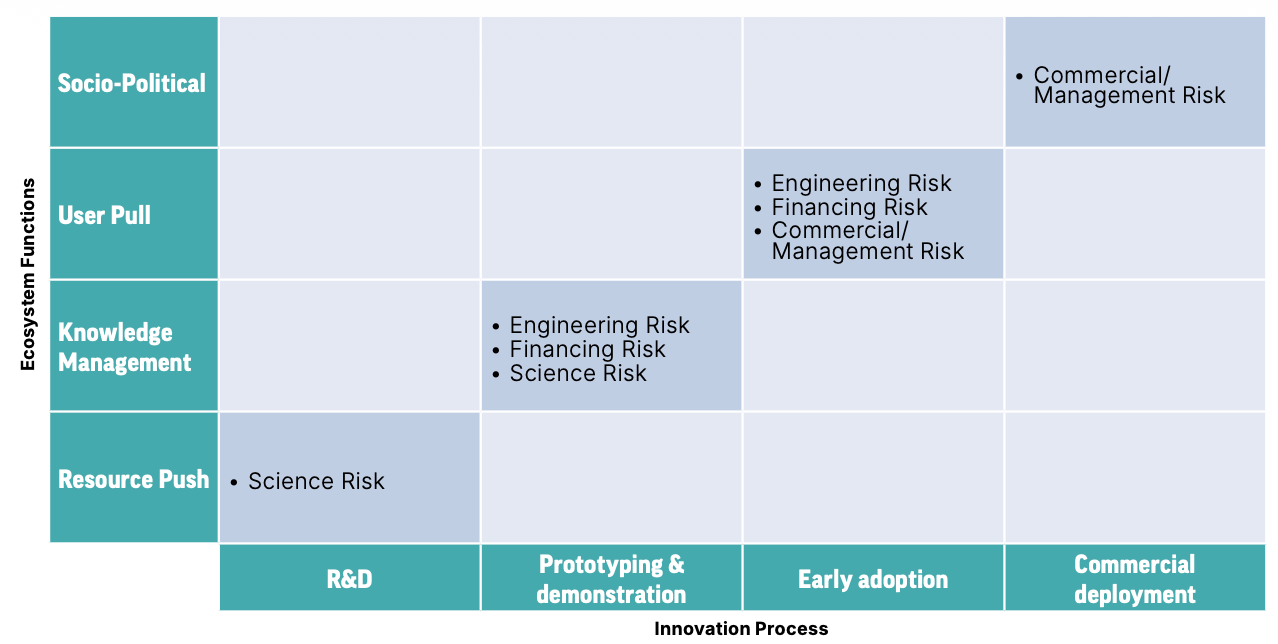

These four functions serve as a helpful lens when trying to understand the nature of a given risk from different perspectives in the ecosystem (see Figure 5). When looking at the resource push function, policymakers can consider how to advance the needs of innovators who are doing the hard work of testing and building new technologies (scientific and engineering risk) and trying to secure investors and customers (financing and commercial & management risk). When looking through the lens of knowledge management, policymakers can consider how to accelerate the different feedback loops across the innovation process to drive down all four types of risk. In the user pull function, policymakers take the view of the demand-side actor, and what prospective investors (financing risk) and customers (commercial & management risk) need to feel a technology is sufficiently derisked (engineering risk) so that they can make their own investments. Lastly, the socio-political support lens ensures that policymakers are not just considering policy through the priorities of supply- and demand-side actors, but also through the impact they will have on communities, workforces, and the public as they are financed and deployed (financing and commercial & management risk).

The following section lays out the final component of the matrix: four key principles of innovation policy, drawing on insights from C2ES’s technology working groups. These are intended to guide federal innovation policy broadly—not only for the technologies featured in our working groups, but for any emerging solution facing similar commercialization barriers. These do not map onto specific functions or stages; rather, they serve as key best practices.

Focus on Building Ecosystems, Not Picking Winners

The role of federal policymakers is not to pick a specific winning company or technology, but rather to foster a robust, and ultimately self-sustaining, innovation ecosystem. Effective policy should unlock both creativity and competition, enabling the best-performing technologies to emerge over time. As developers vie to be selected for limited federal dollars and programs, frontrunners will emerge.

Working group insights

The continuous challenge for policymakers is to strike the right balance between supporting emerging dominant designs while avoiding full technological lock-in. For instance, LDES technologies encompass a diverse range of durations (e.g., inter-day and multi-day) and forms (e.g., electrochemical, mechanical, chemical, and thermal). For this reason, C2ES developed a policy recommendation for the LDES working group on LDES procurement targets.15Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, Policy Recommendations to Unlock the Value of Long- Duration Energy Storage (Washington, D.C.: Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, 2024), https:// www.c2es.org/document/policy-recommendations-to-unlock-the-value-of-long-duration-energy- storage One implementation design option is the establishment of distinct verticals across a range of durations and forms to enable maximum flexibility for utilities, developers, and other power system stakeholders. This policy design enables innovation to progress while avoiding lock-in. This approach also ensures that where there are limited public resources, actors in the ecosystem are competing on comparable performance metrics.

Shoulder Risks Where Private Markets Cannot

The federal government should shoulder appropriate risks—including by removing barriers to innovation—that the private sector cannot manage on its own. This need spans the entire innovation process, from exploratory R&D, through to the incentivization of private investment in commercial projects.

Working group insights

First-of-a-kind projects are often the riskiest and the most difficult to finance—a recurring theme in all four of our technology working groups—as startups work to build their demonstration projects. While venture capitalists have high risk appetites, the capital intensity of these projects often exceeds their threshold, and their payback periods tend to be much shorter than the time required to develop, permit, and construct a large-scale demonstration project. Project finance from institutional investors is typically used to fund these capital-intensive projects, but these lenders have much lower risk appetites. Before they are willing to provide financing, these financiers typically need projects to prove their “bankability.” They do so when a project has sufficiently reduced its commercial, technological, and financial risk to give investors reasonable confidence that it will be profitable.

This threshold is extremely difficult for many early-stage innovations to meet before they build their initial demonstration projects, particularly since much of the derisking and cost efficiencies occur during the ‘learning by doing’ stage of prototyping/demonstration. Federal cost-sharing and grants fill a critical gap here in providing the necessary support for innovations to prove out their technologies via initial demonstration projects. This reality is central to our policy recommendations for the SAF and clean hydrogen working groups, which call for the federal government to provide additional support for demonstration and early commercial-scale projects.16Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, Sustainable Aviation Fuel: Policy Recommendations to Enable a Low-carbon Fuel Mix (Washington, D.C.: Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, 2024), https://www.c2es.org/document/sustainable-aviation-fuel-policy-recommendations-to- enable-a-low-carbon-fuel-mix; see also Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, Clean Hydrogen: Demand-Side Support Policy Recommendations (Washington, D.C.: Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, 2024), https://www.c2es.org/document/clean-hydrogen-demand-side-support-policy- recommendations

Enact Durable Policies to Crowd in Private Capital

Effective innovation policy should have a multiplier effect on private capital. Over time, private sector funding into technologies must meaningfully exceed the amount invested by the federal government. This serves as an important barometer for both the efficacy of the policy and whether the innovation can succeed without perpetual federal support. Inherent in this is the assumption that the policy environment remains sufficiently stable so that financiers and customers have the certainty they need to make longer-term investments and multi-year purchases. Policy stability also enhances policy impact by aligning expectations of all participants in the innovation process.

Working group insights

As noted in the previous principle, securing financing from institutional investors for emerging technologies is a significant barrier on the path to full-scale market diffusion. The same is true for customers. In our working groups, the “green premium,” or the additional cost of adopting nascent clean technologies compared to incumbent technologies, was identified as a significant barrier to scaling demand. Innovation policy can play a role here by offsetting some of the cost for early customers, so that technologies can move down the cost-curve and become more affordable for later customers. Federal tax credits, for example, can reduce or eliminate the green premium by providing a discount on eligible products or lowering the tax burden for customers. Some tax credits also allow transferability, which enables technology developers to sell their credits to third-party buyers for cash. These incentives allow innovators to build revenue streams from nascent technologies and create a customer pipeline, particularly during the early adoption stages of the innovation process.

This was the case in the ECR working group, where both demand- and supply-side players agreed that the 45Q tax credit for carbon sequestration was a major catalyst for the private sector investment in carbon removal technologies. This tax credit helps bridge the gap in the early stages of deployment by reducing costs and attracting investment. As the technology matures and unit costs decline, private investors will be able to carry more of the burden, and the tax credit should phase out. However, at the time of publishing the C2ES ECR policy recommendations (September 2024), higher-than-anticipated inflation had significantly eroded the value of the carbon sequestration tax credit to 87 percent of its initial value.17Congressional Budget Office, “An Update to the Budget and Economic Outlook: 2024 to 2034,” June 2024, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2024-06/60039-Outlook-2024.pdf; see also “Inflation Rate, Average Consumer Price,” International Monetary Fund, updated April 2024, https://www.imf. org/external/datamapper/PCPIPCH@WEO/OEMDC/USA Although the tax credit will be adjusted for inflation in 2027, its value continues to diminish in today’s inflationary environment. This weakens the efficacy and impact of the tax credit for both carbon removal companies and their potential customers. In essence, although the existence of the credit itself is durable (available for twelve years after a project is placed in service), its value is not, since it is not currently indexed to inflation. As a result, one of our key policy recommendations for the working group was to strengthen the credit by incorporating an inflation adjustment in 2024 rather than in 2027.18Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, Engineered Carbon Removal: Markets & Finance Policy Recommendations (Washington, D.C.: Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, 2024), https:// www.c2es.org/document/engineered-carbon-removal-markets-and-finance-federal-policy- recommendations

Align Policy Duration with Technology Commercialization Timelines

Innovation policies should be aligned with real-world commercialization and maturation timelines. Even the most well-designed policy will not be effective if it expires before it can be used by the very innovators it is intended to support. The role of policymakers is to ensure that policies are aligned with the actual needs and pace of the innovation ecosystem.

Working group insights

Innovation takes time, especially in hard-tech sectors. For example, participants in the SAF working group noted existing production tax credits would expire before a new SAF facility could be constructed and start production. Working group members estimated that it takes between five and seven years to fully develop an advanced SAF production facility, while at the time, the 40B sustainable aviation fuel and 45Z clean fuel production tax credits only credited fuels sold within a combined five-year window of eligibility. This finding informed our policy recommendation to establish a production tax credit which allows the taxpayer to commence a fixed duration of eligibility at the time a facility is placed into service, thereby ensuring policy support is consistent with the timeline of SAF project development.19Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, Sustainable Aviation Fuel: Policy Recommendations to Enable a Low-carbon Fuel Mix Since the publication of our SAF policy recommendations in December 2024, the 40B sustainable aviation fuel tax credit has expired. However, in July 2025, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act extended the 45Z clean fuel production tax credit through to December 31, 2029.20). U.S. Congress, One Big Beautiful Bill Act, Public Law No. 119-21, 119th Congress, 1st session (July 2024, 2025). Safe harbor provisions—which enable developers to register their intentions with the Internal Revenue Service and begin construction within a specified time frame to qualify for the credit, even if the facility is placed in service after the expiration of the credit—are another approach that can add flexibility and ensure that policies are aligned with development timelines.

Ideally, as an innovation matures, the ecosystem will become increasingly self-sustaining, with the private sector driving innovation and market development, and outdated policies being phased down over time. This frees up federal funds to support the next generation of technology and ensures that innovation policy continues to advance new technologies as opposed to supporting a new set of incumbents.

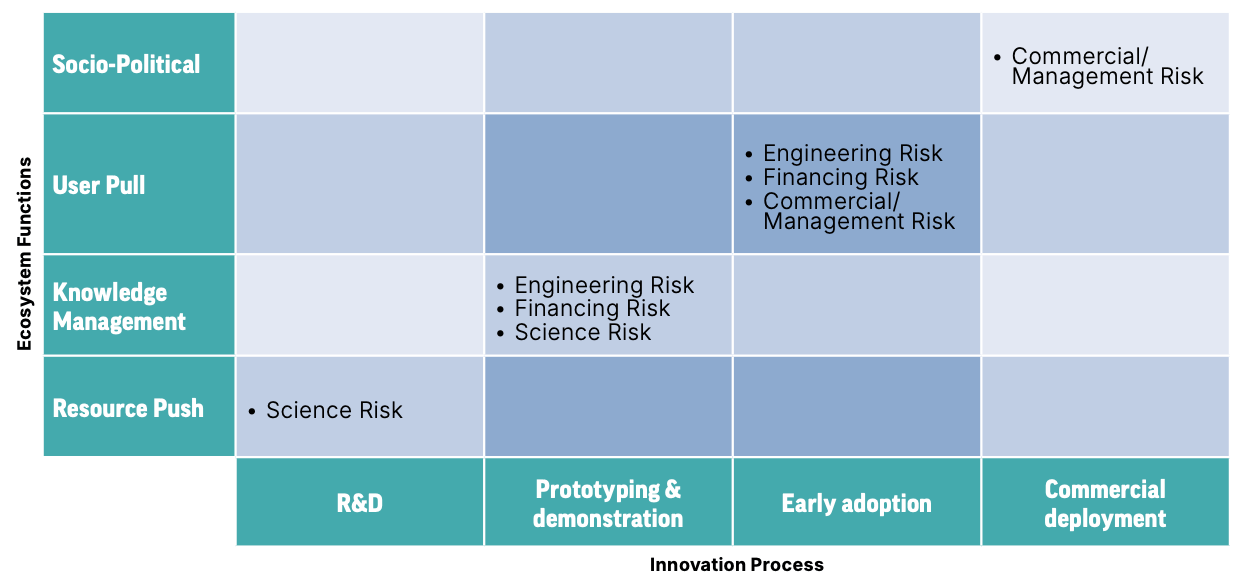

Figure 6 brings together these various components in a single matrix. This matrix is intended to capture the relationship between the different components of the innovation matrix, while also producing a heatmap of where policy need will likely be the greatest. The four stages of the innovation process are placed consecutively along the bottom row of the matrix and the four functions in the leftmost column. The common parameters between the technology-focused innovation process and ecosystem-focused functions are the key risks. These are marked as a diagonal trendline to broadly capture how the nature of risk changes over time, with the caveat that there may be cases where a particular risk appears outside of this general trendline. Similarly, while the ecosystem functions are important across all stages of the innovation process, the matrix highlights periods of heightened risk that can be most effectively mitigated by pairing policies supporting specific ecosystem functions with those addressing particular stages of the innovation process. The policy principles do not formally map onto this matrix, but rather serve as best practices when designing policy interventions to address the key issues identified in the matrix.

As shown in Figure 6, science risk is strongest in the lower left quadrant, where R&D and resource push intersect. Policies in this quadrant will be principally concerned with providing funding and resources to scientists and innovators who are conducting lab-scale research and experiments on novel ideas.

The greatest concentration of risks is found within the middle two quadrants where knowledge management intersects with prototyping and demonstration and user pull intersects with early adoption. Given the confluence of risks, it is no surprise that between these two quadrants lies the “valley of death” for innovators. As innovators work to transition between prototyping and demonstration to early adoption (e.g., first- or second-of-a-kind projects), they are simultaneously grappling with science, engineering, financing, and commercial & management risks. Policy interventions for the second quadrant from the left could include federal cost-shares to help offset high upfront costs, as well as incentivizing strategic partnerships and knowledge sharing between private actors to help accelerate bench-scale prototypes into larger-scale demonstrations. Policy interventions for the third quadrant from the left could include additional cost-sharing, federal procurement, and tax credits to help kickstart market demand for early adoption.

As the innovation reaches commercial deployment and socio-political support becomes increasingly important, commercial & management risk remain dominant concerns. This is the case for all businesses looking to succeed in a competitive private market. At this stage, regulatory and permitting certainty is essential so that innovators and communities have a clear sense of the milestones and requirements that companies must meet as they continue deployment.

The matrix presented in Figure 6 can provide a helpful guide to policymakers in designing innovation policies. Policymakers should select which stages of the innovation process and ecosystem functions are most relevant for an innovation, based on an assessment of the factors discussed above. Those horizontal and vertical rows can then be shaded, marking the intersection a deeper color. The matrix now serves as a heatmap for where the policy need is likely greatest.

An illustrative example using the C2ES technology working groups is provided below.

Most of the companies in the working groups have addressed the scientific risk of their technologies, and are squarely focused on engineering, financing, and commercial & management risks. All of these risks suffer from the ‘chicken and egg’ problem, where companies need to secure financing and early-stage customers to build their pilots and demonstration projects, but investors and customers first want to see the technology proven out before providing capital. This creates a “valley of death” where many companies are unable to progress beyond early pilot scale.

The innovators in the working groups tend to be the leading companies in their field and are the first movers forging the path toward commercialization. Across all four working groups, startups and corporate partners are in the process of building first-of-a-kind facilities, with an eye toward sufficiently demonstrating and derisking their technologies so they can rapidly scale toward commercial deployment. As a result, most of the startups in the working groups are at the prototyping and demonstration stage, with some having moved into the early adoption stage (see Figure 7).

Discussions with working group companies revealed salient challenges between supply- and demand-side actors, which mapped closely onto the resource push and user pull ecosystem functions. Emerging technologies face significant cost and adoption hurdles, and private actors can be hesitant to provide capital during this high-risk stage. Reliable demand also depends on robust supply-side foundations, including infrastructure, permitting, and production capacity. Without these elements, even strong market interest cannot translate into deployment.

;

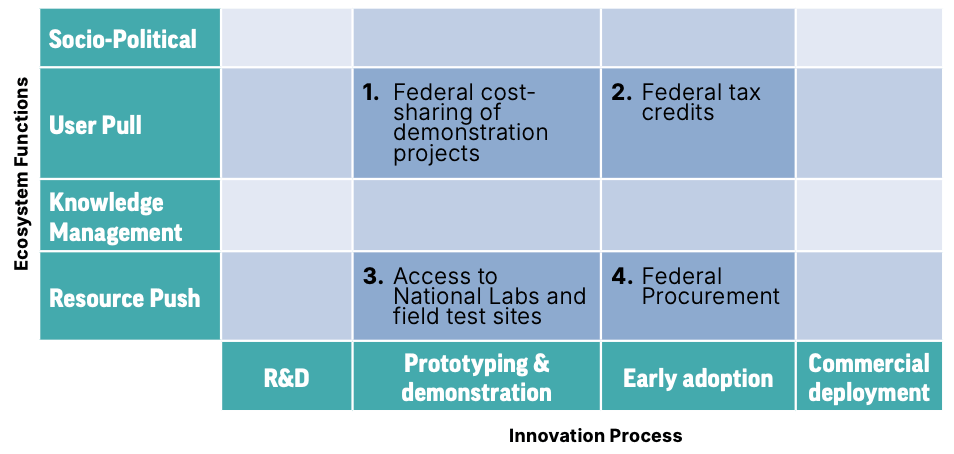

As discussed, the technology working groups are most focused on addressing risks in the prototyping & demonstration and early adoption stages, particularly as it relates to the functions of user pull and resource push. This indicates that there are four key quadrants where the policy need will be the greatest (see Figure 9).

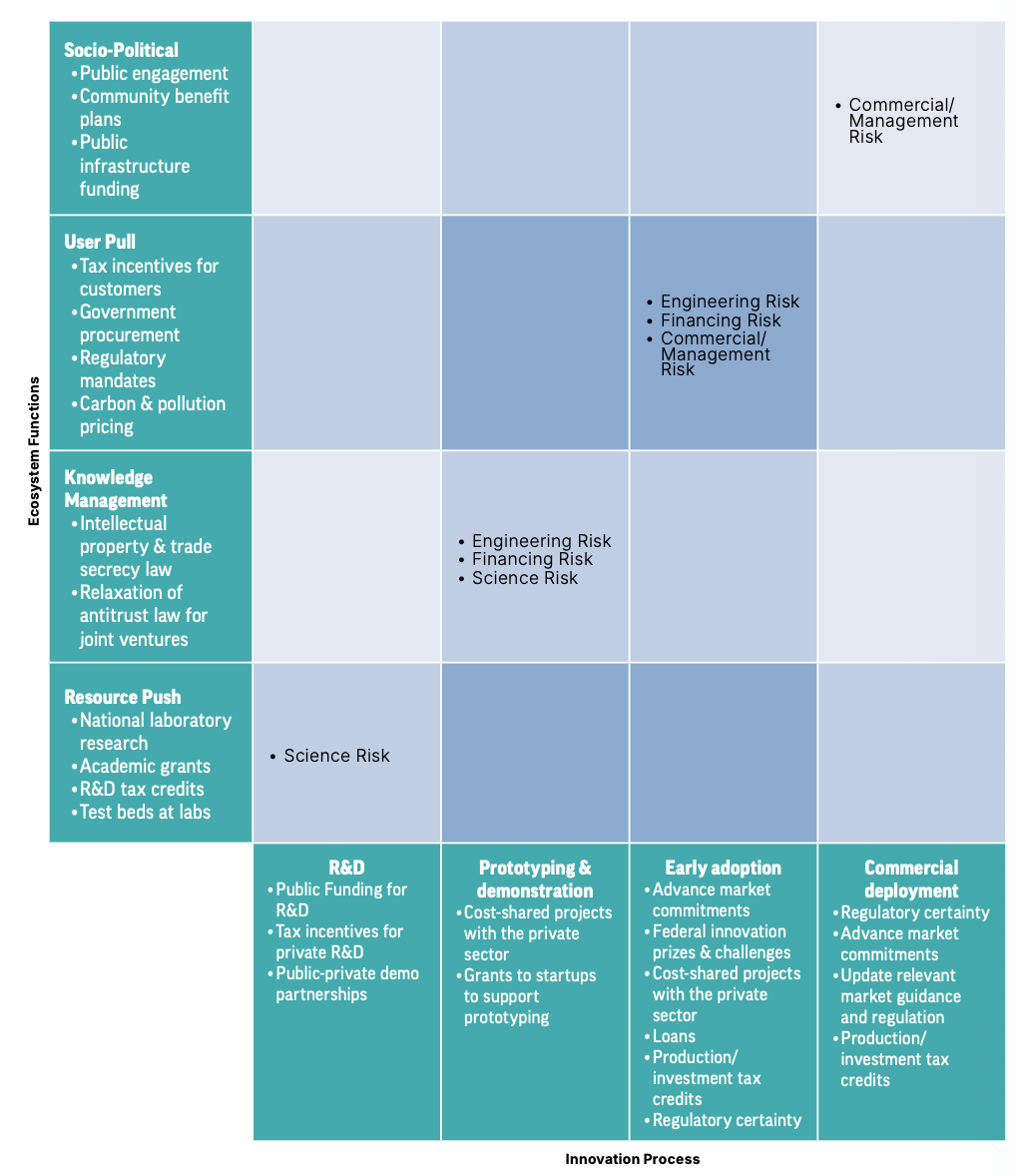

The matrix elucidates which areas to prioritize in policymaking, but the question remains on what specific policies should be pursued. The universe of potential innovation policies is vast and varied, but certain types of policies have proven to be particularly effective at advancing innovation and unlocking bottlenecks in the ecosystem. A sample set is provided below (see Figure 10), mapped against the specific innovation process and ecosystem functions that the policy addresses. In many cases, the same policy can span multiple stages of the innovation process or ecosystem functions. For example, federal procurement of a technology benefits both innovators (resource push), and prospective customers (user pull). The key is to think about the policy through the lens of the specific stage, function, and risk that needs to be addressed.

This paper presents a framework for policymaking that is intended to support the accelerated commercialization of innovative technologies. The C2ES Innovation Policy Matrix outlines the key components that policymakers need to consider when assessing and designing policies; the risks policy is attempting to mitigate; the technology’s stage of development; and the context provided by the ecosystem function that policy is intended to support. This matrix builds on the latest thinking in innovation policy, while aiming to reflect the complexity of real-world conditions drawn from an important—and often overlooked—set of company perspectives from across the value chains of nascent, but promising technologies. By utilizing the C2ES Innovation Policy Matrix, policymakers can better diagnose the federal policy support necessary to enable an environment where the most promising innovations can succeed. In the future, C2ES intends to expand on the matrix through both continued exploration of the current technology set as well as additional critical-path technologies that are emerging in new market and regulatory contexts.

Innovation and the policies enacted to support it are often constrained by political realities, including the difficulty of modifying existing incentives that may have outlived their purpose, and regulatory constraints that discourage new approaches, which tend to inhibit innovation by favoring existing incumbents. Further, much of the policy discussions surrounding innovation to date have—understandably—focused on ensuring government programs that support innovation are properly resourced. This can result in a fragmented policy landscape, where political incentives encourage the avoidance of risk and the political scrutiny that accompanies failure. In truth, a key goal should be to embrace the risks that the private sector cannot. Further, while significant federal investments are necessary for a healthy innovation ecosystem, they are not alone sufficient. Tailoring those investments to the specific technological, market, and regulatory challenges faced by innovators, with a clear and specific purpose, not only better supports innovation, but can also establish clear timelines for when specific policies have outlived their utility. This approach can also more efficiently use limited resources, while reducing the risk that the federal government invests in projects that the private sector is better positioned to pursue. Balancing durability with clearly defined objectives and sunsets for policy interventions can also provide the private sector the certainty it needs to make larger bets on the innovative technologies that will define the 21st-century economy and beyond.