Physical climate impacts are fundamentally reshaping the risk landscape for global businesses. Through six dialogues conducted in 2025, the Climate Resilience Foresight Series brought together leaders from two dozen companies to explore how organizations can build comprehensive resilience to climate change. This synthesis presents a strategic framework for corporate climate resilience, drawing on insights from participants across manufacturing, energy, technology, financial services, and other critical sectors.

The dialogues revealed that while awareness of climate risks has grown substantially, translating this awareness into sustained action remains challenging. Companies face genuine barriers including competing priorities, data limitations, and governance structures not designed for long-term, systemic threats. Yet leading organizations are developing innovative approaches that frame resilience as a source of competitive advantage rather than merely a cost center. As climate impacts accelerate, the companies that systematically build adaptive capacity will be best positioned to protect value, seize opportunities, and contribute to broader societal resilience.

The World Economic Forum’s 2024 Global Risks Report identifies climate-related threats among the top three risks testing organizational resilience.1World Economic Forum, “Global Risks Report 2024,” World Economic Forum, January 10, 2024, https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-risks-report-2024. Organizational resilience can be defined as ensuring that businesses can anticipate, absorb and adapt to a changing environment while continuing to deliver value to stakeholders.2Resilience First, “Organisational Resilience,” Resilience First, 2024, https://resiliencefirst.org/ what-we-do/organisational-resilience. For global companies, physical climate impacts—from extreme heat and flooding to supply chain disruptions and workforce challenges—are no longer hypothetical scenarios but operational realities demanding a strategic response.

The Climate Resilience Foresight Series, a partnership between Resilience First, based in the United Kingdom, and the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (C2ES), based in the United States, was designed to help large businesses navigate this evolving landscape. Through six strategic dialogues conducted between March and September 2025, the series convened senior resilience leaders from across sectors to share approaches, challenges, and emerging practices for improving organizational resilience to physical climate impacts.

The series employed Resilience First’s standards-aligned Model for Organizational Resilience, which examines climate impacts across five essential dimensions:3Resilience First, “Introduction to a New Model for Organisational Resilience,” Resilience First, 2024, https://resiliencefirst.org/news/introduction-new-model-organisational-resilience.

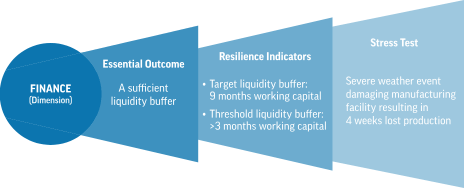

Using the model’s measurement-driven approach to resilience, series participants first identified business and service outcomes for each dimension of their organization that would be affected by climate shocks. They then explored potential indicators that could help understand how resilient this dimension of their organization is to climate change. Finally, participants discussed initial ways they could stress test the resilience of these outcomes. Figure 1 is an illustrative example. It posits an essential financial outcome, which resilience indicators would lead to the desired outcome, and a climate-related stress test. Additional examples of potential climate resilience are included in the Appendix.

A sixth dialogue focused on corporate governance—the critical overlay that determines how organizations integrate climate resilience across all dimensions. This governance lens revealed the organizational structures, decision-making processes, and leadership engagement that ultimately determine whether climate resilience moves from aspiration to implementation.

This synthesis distills insights gleaned from over 40 participants representing 24 organizations from different industry sectors and geographies, including food and beverage, technology, telecommunications, electric utilities, rail, chemicals and manufacturing, construction, banking, and insurance. These several insights from the series coalesce around common areas to address that would enable companies to protect value and maintain competitiveness, and, in doing so, contribute to the resilience of the communities in which they operate.

The dialogues revealed a fundamental insight: climate resilience cannot be achieved alone. Companies consistently reported that their greatest vulnerabilities often lie outside their direct control—in supply chains, infrastructure systems, workforce communities, and natural ecosystems. This systemic nature of climate risk requires a corresponding evolution in how businesses approach resilience.

Participants shared numerous examples of cascading failures triggered by climate events. A technology company described how flooding at a single supplier facility created months of production delays across multiple product lines. A major utility owner and operator reported that extreme heat not only stressed grid infrastructure but simultaneously increased demand, reduced generation efficiency, and threatened worker safety—creating compound operational challenges that individual risk assessments had failed to anticipate. Both examples show how disruptions in one business segment can have cascading effects across an organization.

These cascade effects manifest across multiple pathways:

Across all dialogues and sectors, two climate impacts emerged as universal business threats: extreme heat and water stress. These impacts transcend geographic and sectoral boundaries, affecting every dimension of organizational resilience.

Extreme heat creates multiple simultaneous challenges. Manufacturing companies reported equipment failures and reduced operational efficiency. The construction and agriculture sectors face severe constraints on outdoor work, with some regions approaching physiological limits for human labor and severe supply chain delays due to heat-ruptured transport systems. Data centers—now considered to be critical national infrastructure in many countries—and technology infrastructure require exponentially increasing cooling capacity.

Financial services firms are considering how to price heat-related productivity losses into investment decisions. Notably, while many of the firms noted extreme heat challenges facing outdoor workers, many companies face challenges with lack of air conditioning in supplier facilities, often located in the Global South, that have similar impacts on workers.

Water stress—encompassing both scarcity and excess—similarly cuts across organizational boundaries. Semiconductor manufacturers described how water shortages threaten production capacity. Food and beverage companies face fundamental constraints on raw material availability. Energy utilities must balance cooling needs with environmental regulations. Real estate firms are reassessing portfolio values based on flooding risk and water availability.

The universality of these threats suggests that companies’ climate adaptation strategies will prominently feature heat and water resilience. Companies that develop robust approaches to managing these risks will likely address a significant portion of their climate vulnerability while building capabilities applicable to other climate impacts.

Leading global insurers are issuing urgent warnings that corporations can no longer assume ongoing insurance coverage will remain available or affordable without proactive climate resilience measures, as rising climate-related losses fundamentally threaten the viability of traditional insurance markets.

Marsh McLennan’s 2023 report emphasizes that without investment in adaptation and resilience, climate change may drive weather-related risks in certain regions to levels that are no longer insurable, eroding markets and shrinking profit pools—a phenomenon already evident in the Western United States due to wildfire threats and contributing to the establishment of catastrophe risk pools in vulnerable regions.4Marsh, “Insurance as a Key Catalyst for Climate Action,” Marsh, October 22, 2025, https://www.marsh.com/en/services/climate-change-adaption/insights/insurance-as-a-key- catalyst-for-climate-action.html. 5Marsh McLennan, “Building a Climate Resilient Future,” Marsh McLennan, 2023, https://www.marshmclennan.com/web-assets/insights/publications/2023/decem- ber/2023-marsh-mcLennan-building-a-climate-resilient-future.pdf.The industry currently faces a $142 billion global protection gap, with only 46 percent of weather-related losses insured, while insured losses from natural catastrophes have more than doubled relative to global gross domestic product (GDP) since 1994. Zurich Insurance warns that the growing volatility of climate disasters demands corporations reframe their approach beyond traditional risk transfer toward risk prevention, reduction, and resilience-building strategies.6Zurich, “Strategies for Building Resilience in a More Volatile World,” Zurich, April 29, 2025, https://www.zurich.com/knowledge/topics/climate-change/strategies-for-building-re- silience-in-a-more-volatile-world. AXA’s 2025 Future Risks Report reinforces this message, stating that the insurance industry is undergoing one of its greatest transformations by shifting from paying claims to preventing those claims from arising, requiring a fundamental change in mindset and technology to help people better prepare for the unexpected.7AXA, “Future Risks Report 2025,” AXA, October 13, 2025, https://www.axa.com/en/press/publications/future-risks-report-2025-report. All three insurers emphasize that companies demonstrating measurable risk reduction through climate resilience investments—including infrastructure hardening, nature-based solutions, improved building standards, and enhanced disaster preparedness—can benefit from potentially more favorable premium pricing, maintained insurability, and protection of existing markets, while those that fail to adapt face the prospect of becoming uninsurable as climate risks accumulate and traditional underwriting models become economically unsustainable.

The corporate governance dialogue revealed that organizational structures and decision-making processes fundamentally determine resilience outcomes. While technical solutions and financial resources are necessary, they prove insufficient without governance systems that embed climate considerations into core business processes.

A striking finding from the governance dialogue was the persistent gap between risk perception and action. Survey data presented by Marsh revealed that while 60 percent of organizations feel they have sufficient resources to address climate risks, only 45 percent of resilience spending targets long-term adaptation rather than short-term continuity. This misalignment may reflect deeper governance challenges:

Leading companies are working internally to foster and support governance structures that embed climate resilience into decision-making. Several potential models emerged from the dialogues:

One large technology company employs dedicated climate teams that work across the organization to embed resilience considerations within organizational functions. These teams report to senior operational leadership—as opposed to sustainability functions, which ensures direct connection to business decision-making. Regular cadences, such as monthly steering committees and quarterly working groups, maintain momentum and accountability.

One electric utility integrates climate risk across multiple board committees rather than siloing it in a single sustainability committee. This approach ensures that climate considerations inform audit, risk, compensation, and strategy discussions. While the model enables climate risk to be a core business concern with board-level oversight, such a structure still requires the board to enable decision-making on climate risk, rather than treating climate risk only as a topic of interest to be monitored.

Engineering-intensive companies have found success by embedding climate projections directly into design standards and operational procedures. One telecommunications company developed climate risk scores that became mandatory considerations for all infrastructure investments. This approach leverages existing governance mechanisms rather than creating parallel processes.

One approach involves structured frameworks that measure resilience across multiple organizational dimensions. The Model for Organizational Resilience, developed through partnership between Cranfield University and Resilience First, employs five core dimensions—social, financial, workforce, infrastructure, and environment—to guide strategic planning. Organizations using this model establish Essential Outcomes to prioritize critical functions, deploy Resilience Indicators that set performance targets for both normal and severe conditions, and conduct regular stress testing to identify vulnerabilities. This framework enables companies to move beyond theoretical resilience planning toward data-driven decision-making that directly connects to business outcomes. While the model provides comprehensive structure, successful implementation requires organizations to customize indicators to their specific operational context rather than applying generic metrics.

Participants identified several persistent barriers to effective climate governance and strategies for overcoming them:

Crisis Preparedness: Organizations often require a crisis to catalyze action. Some companies simulate climate disruptions through scenario planning and war gaming exercises, creating “synthetic crises” that build organizational muscle memory without actual losses.

Competing Priorities: With key issues such as artificial intelligence (AI), digital transformation, and increased energy demand competing for resources, climate resilience struggles for attention. Framing climate resilience as an enabler

of other strategic priorities—protecting AI infrastructure, ensuring digital resilience—rather than a competing initiative, may garner more interest and investment from leadership.

Leadership Turnover: Executive changes can shift attention from previously supported resilience initiatives. Organizations that embed climate considerations into role transitions, succession planning, and institutional knowledge management are more likely to maintain continuity despite personnel changes.

The dialogue series examined climate resilience through five interconnected dimensions: environment, infrastructure and operations, workforce, finance, and social and external ecosystems. Each of which revealed both dimension-specific strategies and critical interdependencies. Organizations achieving comprehensive resilience recognize that actions in one dimension create ripple effects across others.

Companies increasingly recognize that business resilience depends fundamentally on ecosystem health. Dialogue participants from agriculture, food and beverage, and manufacturing sectors described how environmental degradation directly threatens operational viability.

Key strategies include:

A food and agriculture company shared how investing in watershed restoration not only secured water supplies but also strengthened community

relationships and reduced regulatory risk. However, participants noted that most environmental initiatives remain reactive—responding to degradation rather than proactively building ecosystem resilience. A proactive approach is optimal because then companies can mitigate the causes of climate change while building resilience to the impacts that are locked in.

Infrastructure adaptation represents the most tangible aspect of climate resilience for many companies. While participants described substantial investments in physical hardening (e.g., flood barriers and enhanced cooling systems), the dialogue revealed that effective infrastructure resilience extends beyond physical assets. It encompasses supply chains, logistics networks, and operational flexibility.

Key strategies include:

One electric utility’s multi-billion dollar investment in grid hardening exemplifies the scale of infrastructure adaptation required. However, the company emphasized that physical hardening alone proves insufficient—operational changes, predictive maintenance, and community coordination are equally critical.

Climate impacts on workforce productivity, health, and safety emerged as a critical concern across sectors. Companies are expanding beyond traditional occupational safety to address heat stress, climate anxiety, and community disruption affecting employees.

Key strategies include:

Construction and utility companies reported that extreme heat is already constraining work schedules, with some regions experiencing 20–30 percent productivity losses during summer months. While addressing the human dimension of climate resilience presents new challenges, enabling workforce health and productivity can also provide the most tangible and immediate benefits.

Making the business case for resilience investments remains challenging, yet participants identified multiple pathways for demonstrating value, such as through expanding analysis beyond cost avoidance to capture revenue protection, competitive advantage, lower future debt and costs, and additional value.

Key strategies include:

Insurance sector representatives warned that assuming continued coverage availability is increasingly risky. Some companies—such as one large tech company who participated in the dialogues—are already preparing for conditions where some risks become uninsurable, requiring greater self-insurance and risk retention.

Climate resilience cannot be achieved in isolation. Communities, suppliers, and other stakeholders are also key to ensuring long-term climate resilience. Participants emphasized that organizational resilience depends on the resilience of the broader communities, as well as of the infrastructure and social systems in which they all operate.

Key strategies include:

One technology company’s approach of embedding resilience requirements into supplier contracts demonstrates how large purchasers can drive adaptation throughout value chains. However, smaller suppliers often lack resources and expertise, requiring capability-building support to be able to comply with new requirements.

A consistent theme across all dialogues was the challenge of obtaining actionable climate data and developing meaningful resilience metrics. While climate science has advanced substantially, translating projections into business-relevant information remains difficult.

Companies face multiple data-related challenges:

Participants emphasized the importance of taking action and not letting the lack of perfect, granular data hinder or constrain decision making. Companies making progress on resilience have learned to act on directional insights while continuing to refine their data and models.

Despite challenges, new tools and methodologies are enhancing climate risk assessment:

Several companies described success with “climate risk scores.” These are simplified metrics that translate complex climate data into actionable decision tools. One large telecommunications provider integrated climate scores into all infrastructure planning, exemplifying this approach.

Organizations struggle to define and measure resilience in ways that resonate with leadership and stakeholders. Even with the use of resilience models that identify business outcomes and resilience indicators, turning these metrics into business decisions is a challenge.

Effective metrics share several characteristics. They are:

Examples of metrics that companies are beginning to develop include: days of operation lost to climate events, percentage of critical assets with resilience plans, heat-related safety incidents, water intensity per unit of production, and percentage of suppliers with climate assessments. See the Appendix for examples of additional metrics.

Effective communication about climate resilience—both internal and external—emerged as a critical success factor. Companies must navigate diverse stakeholder perspectives, from executives to local community leaders, requiring targeted messaging strategies.

Participants shared successful approaches for building internal support:

Audience-specific framing: Engineers respond to technical risk assessments, finance teams to ROI calculations, and operations to continuity impacts. Successful climate champions learn to translate resilience into each function’s “language.”

Concrete over abstract: “The transformer failed three times last summer” resonates more than climate projections. Companies should anchor discussions in observed impacts and near-term consequences.

Positive positioning: Framing resilience as competitive advantage, innovation catalyst, and growth enabler proves more effective than risk-focused messaging alone.

Peer comparisons: “Our competitors are doing X” creates powerful motivation. Several participants emphasized that sharing what peers are doing helps convince leadership to act.

A surprising consensus emerged from the dialogues: companies seek more external pressure on climate resilience. Participants consistently reported that customer requirements, investor expectations, and regulatory frameworks provide essential leverage for securing internal resources and attention.

Key external drivers include:

This desire for external pressure reflects the difficulty of maintaining momentum on long-term challenges within short-term oriented business cultures. External requirements provide an important impetus needed to justify resilience investments that may not deliver returns on investment within typical planning horizons

Based on insights from across the dialogue series, several proposed strategies emerge for companies seeking to build comprehensive climate resilience. These proposed strategies reflect how some leading companies are beginning to address the common barriers identified throughout the discussions and where new efforts are needed to scale climate resilience across all organizational dimensions.

Throughout the dialogues, companies referred to lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic, which provided a real-world test of organizational resilience, and where organizations demonstrated that they possess remarkable capacity for rapid transformation when necessity demands it. Within weeks, companies overhauled operations, deployed digital tools at unprecedented scale, enhanced supply chain visibility, and adapted workforces to new operating models. Organizations with existing scenario plans proved more agile, validating that general preparedness frameworks could also be directly relevant to climate resilience.

However, pandemic experience also reveals potential impediments. Success navigating COVID-19 may lead organizations to overestimate existing capabilities for future challenges, while prior failure could reinforce fatalistic views. Organizational exhaustion from prolonged crisis response may have reduced appetite for preparing for new disruptions precisely when sustained adaptation is most needed.

Effective organizations recognize differences between pandemic response and climate adaptation. Climate impacts are predictable in direction, requiring sustained strategic effort and long-term planning rather than rapid emergency response. The pandemic’s most valuable lesson is that transformative change is possible when organizations recognize necessity. The challenge is creating that sense of necessity and urgency before catastrophic climate impacts force reactive responses. Companies must translate proven capacity for rapid adaptation into sustained, proactive transformation.

Throughout the dialogues, participants shared insights on how different roles within companies can help advance climate resilience across all business dimensions. Most insights corroborated best practices from other recent publications examining how businesses leaders can strengthen climate resilience, including the World Business Council for Sustainable Development’s (WBCSD) Business Leader’s Guide to Adaptation and Resilience,8WBCSD, “The Business Leader’s Guide to Climate Adaptation & Resilience,” WBCSD, 2024, https://www.wbcsd.org/resources/the-business-leaders-guide-to-climate-adaptation-resilience. WBCSD’s Physical Risk and Resilience in Value Chains: CEO Handbook on Executive Engagement,9WBCSD, “Physical Risk and Resilience in Value Chains,” WBCSD, 2025, https://www.wbcsd.org/ resources/physical-risk-and-resilience-in-value-chains. and the World Economic Forum’s The Cost of Inaction: A CEO Guide to Navigating Climate Risk.10 World Economic Forum, The Cost of Inaction: A CEO Guide to Navigating Climate Risk, 2024, https://reports.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Cost_of_Inaction_2024.pdf.

Based on discussions among dialogue participants, the following key actions will help integrate resilience across all business units, build the value proposition for investing in resilience, and develop greater accountability and ownership at the executive and unit level for advancing climate resilience.

The transition from climate awareness to action requires fundamental shifts in how organizations perceive and manage risk. It necessitates a governance structure that balance short-term pressures with long-term imperatives, new forms of collaboration that recognize the systemic nature of climate threats, and calls for leadership that frames resilience as an investment in sustainable business success.

The dialogues revealed that leading companies are taking action to build resilience to a changing climate. They are developing innovative approaches that deliver multiple benefits across business dimensions; engaging in partnerships to address systemic risks beyond individual organizational boundaries; and exploring where climate resilience can drive innovation, strengthen stakeholder relationships, and create new sources of competitive advantage.

Companies face genuine barriers to building resilience, including data limitations, governance challenges, and the difficulty of justifying long-term investments in short-term-oriented business cultures. The systemic nature of climate risk means that individual organizational resilience, while necessary, is insufficient. Success requires coordinated action across businesses, governments, and civil society. Companies that act decisively now by embedding resilience into strategy, operations, and culture will be best positioned to navigate the disruptions ahead.

Three key enablers affect pace and scale of building corporate climate resilience:

While climate change presents a substantial risk to companies, those that transform risk into opportunity and begin to build resilience across all organizational dimensions will be positioned to thrive in the climate-altered economy going forward.