Extreme heat—periods of unusually high temperatures that threaten human health, ecosystems, and infrastructure—is becoming more frequent and intense as the climate warms. Communities across the United States are already experiencing longer heat seasons, more dangerous heat index days, and greater risks to vulnerable populations.

Historical Conditions and Future Projections for Heat

Across the globe, hot days are getting hotter and occurring more frequently. The year 2024 was the hottest year on record, with global average temperatures more than 1.5 °C above the 1850-1900 average. The past 10 years, from 2015 to 2024, were the hottest on record globally. In cities across the United States, the average rate of extreme heat events increased from two per year in the 1960s to ten per year between 2010 and 2020. Additionally, as of 2024, the average length of heat-wave season in the U.S. has increased by 46 days since the 1960s.

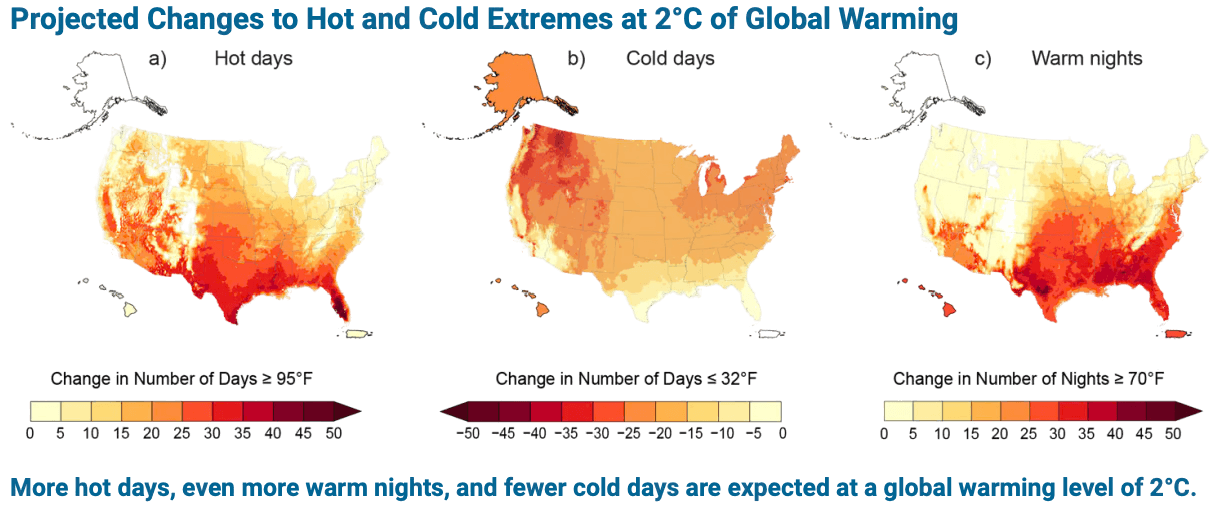

Looking ahead, the Fifth National Climate Assessment estimates that most areas of the United States will experience 15–30 more days over 95°F per year with 2°C of global warming. Some places, like Florida, could experience up to 50 more days over 95°F per year under this scenario, while the Northeast may only experience an increase of 5–15 days over 95°F per year.

Heat waves are more dangerous when combined with high humidity. The heat index measures the combination of temperature and humidity. A 2019 study projected that nationwide over the coming century, the annual number of days with a heat index above 100°F will double and days with a heat index above 105° F will triple, compared to the end of the 20th century.