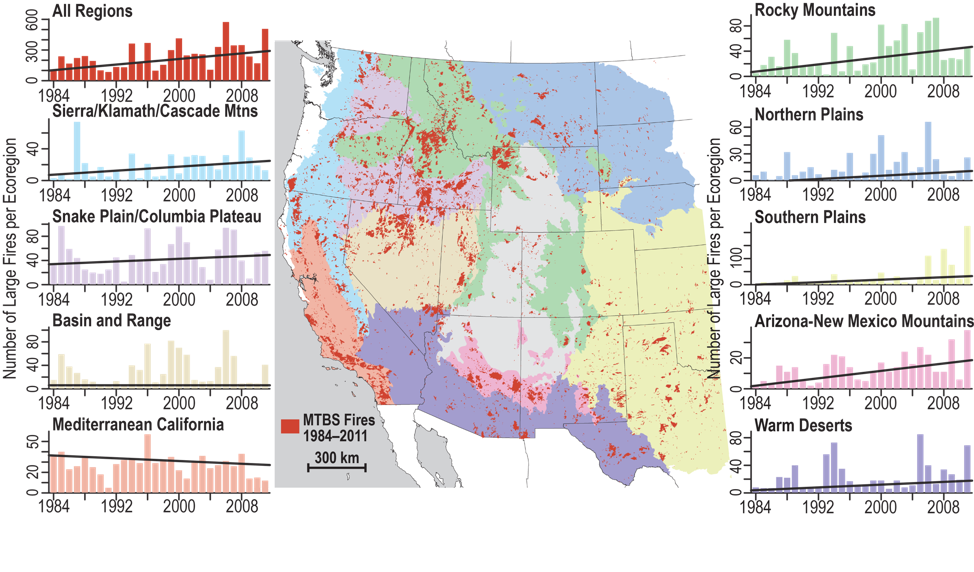

Climate change has been a key factor in increasing the risk and extent of wildfires in the Western United States. Wildfire risk depends on a number of factors, including temperature, soil moisture, and the presence of trees, shrubs, and other potential fuel. All these factors have strong direct or indirect ties to climate variability and climate change. Climate change enhances the drying of organic matter in forests (the material that burns and spreads wildfire), and has doubled the number of large fires between 1984 and 2015 in the western United States.

Research shows that changes in climate create warmer, drier conditions. Increased drought, and a longer fire season are boosting these increases in wildfire risk. For much of the U.S. West, projections show that an average annual 1 degree C temperature increase would increase the median burned area per year as much as 600 percent in some types of forests. In the Southeastern United States modeling suggests increased fire risk and a longer fire season, with at least a 30 percent increase from 2011 in the area burned by lightning-ignited wildfire by 2060.

Once a fire starts—more than 80 percent of U.S. wildfires are caused by people—warmer temperatures and drier conditions can help fires spread and make them harder to put out. Warmer, drier conditions also contribute to the spread of the mountain pine beetle and other insects that can weaken or kill trees, building up the fuels in a forest.

Land use and forest management also affect wildfire risk. Changes in climate add to these factors and are expected to continue to increase the area affected by wildfires in the United States.